What Impact Did Zheng He's Travels Have

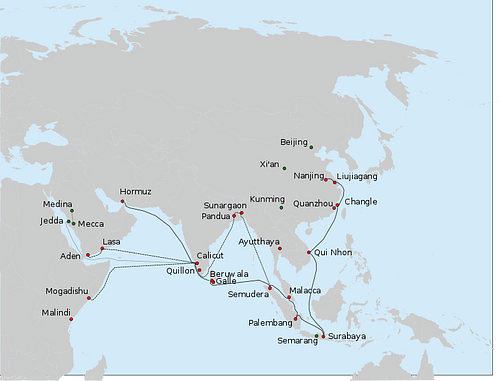

Admiral Zheng He (aka Cheng Ho, c. 1371-1433 CE) was a Chinese Muslim eunuch explorer who was sent by the Ming dynasty emperor Yongle (r. 1403-1424 CE) on seven diplomatic missions to increment merchandise and secure tribute from foreign powers. Between 1405 and 1433 CE Zheng He commanded huge fleets loaded with trade goods and high-value gifts to such far-flung places as Hormuz in the Persian Gulf and Mogadishu in East Africa. Following established bounding main routes merely ofttimes finding himself the starting time ever Chinese person to country at many of his destinations, Zheng He is widely regarded every bit the greatest always Chinese explorer. His travels may not have brought much success in terms of new trade or lasting tribute to the majestic court only the knowledge, ideas, and exotic appurtenances he brought back home - from jewels to giraffes - created an involvement in foreign countries and a realisation of their wealth which contributed to Cathay'due south increased role in world trade in later centuries. Even if his wake was not immediately followed, Zheng He had shown the way.

Chinese Junk Ship

Yongle Emperor's Strange Policy

1 of the indelible symbols of the Ming dynasty's eagerness to extend international relations under its 3rd emperor, Yongle, is the seven ocean voyages of Zheng He. Yongle'due south predecessors had been cautious to the point of isolationism when it came to foreign affairs, largely out of fright of military conquest past neighbouring peoples, especially the Mongols. More secure on his imperial throne, and having grabbed it in the first place afterward a three-year civil war, Yongle perhaps sought some international legitimacy for his position as emperor.

Traditionally, Tribute from abroad had confirmed the Chinese vanity that their ain culture was superior to all others.

The traditional presentation of tribute to Chinese emperors past other, smaller states in Southeast Asia was given to prevent invasion or accomplish a theoretical hope of protection in the instance of invasion by a third party or because diplomatic missions giving that tribute were permitted to behave trade while in Mainland china. The tribute, unremarkably far less valuable than the appurtenances which the emperors gave out, had always been a badge of approval to the Chinese, indicative that their emperor was indeed the Son of Heaven and the nearly powerful ruler on globe. Information technology likewise confirmed the Chinese vanity that their own culture was superior to all others. The organization had lapsed during the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1276-1368 CE) but Yongle wanted to revive information technology. What better way to convince the powerful officials of the purple bureaucracy that he was the chosen one than having strange ambassadors prostrate themselves in the Forbidden City and offer upward a handsome sample of the riches of their country?

Another possible motive, at to the lowest degree for the earlier voyages to Southeast Asia, may have been to discover the whereabouts of the deposed emperor Jianwen (r. 1398-1402) and so ensure he did not stir up a rebellion to accept dorsum his throne from his usurper Yongle. The scale of the fleets involved has also led some scholars to propose the expeditions were rather more interested in some grade of colonialism than mere diplomacy and merchandise, simply this view is not widely held.

Admiral Zheng He

Yongle would acceleration many diplomatic missions across country routes to such places as Samarkand and Tibet but the human selected to lead the emperor's most important maritime forays into foreign diplomacy was Zheng He. Born into a Muslim peasant family unit in Yunnan province in southern People's republic of china c. 1371 CE, his family-given proper name was Ma Ho. The future explorer would take a difficult childhood but he certainly had the travel problems in his veins as his father had made the Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca. Living in a region of China that was then controlled by the Mongols, Ma Ho was captured past Ming forces at the historic period of ten. In the typical treatment of those captured in warfare and destined to be slaves or servants, Ma Ho was castrated. He was and so conscripted into the army commanded by a Ming prince, none other than the future emperor Yongle. Ma Ho'south talents saw him progress through the ranks, beingness selected as the head eunuch and becoming an of import support to Yongle's claim for the throne. When Yongle won a three-year ceremonious state of war and became emperor in 1403 CE, Ma Ho was given the new proper name of Zeng He (aka Cheng Ho).

Zheng He

India & Sri Lanka

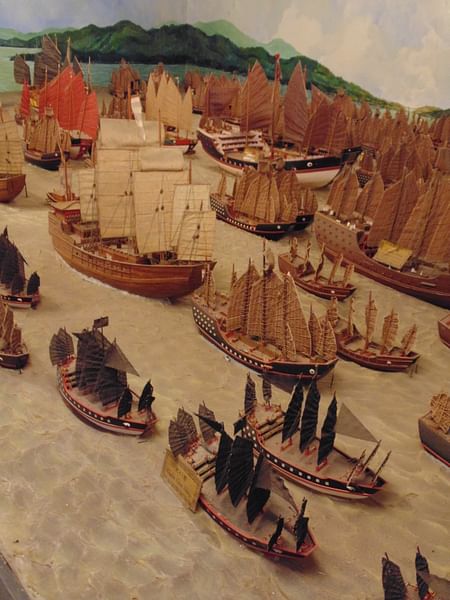

By 1405 CE Zheng He was an admiral in the imperial fleet, and he was selected by the emperor to lead a fleet beyond the Indian Ocean to explore the possibilities of new tributary states and bring them into the sphere of Chinese influence. The massive fleet of 317 ships had been under construction since 1403 CE and included 62 baochuan, then the largest ships in the world. These Chinese junks, too known as 'treasure ships', were possibly up to 55 metres (180 ft) in length and 8.5 metres (28 ft) wide (although the verbal dimensions are disputed amid historians). The junks Zheng had in his fleet would not accept been significantly different from those described as follows by the famed Muslim traveller from Tangier Ibn Battuta (1304 - c. 1368 CE):

The large ships have anything from twelve down to iii sails made of bamboo rods plaited similar mats. A ship carries a complement of a yard men…The vessel has four decks and contains rooms, cabins and saloons for merchants.

(quoted in Brinkley, 170)

Many of the vessels, congenital at the shipyards of Nanjing, were equipped with such innovations as h2o-tight compartments, sternpost rudders, magnetic compasses and paper charts and maps. The ships were packed with fresh h2o, food supplies, and Chinese luxury appurtenances intended to woo strange rulers into displaying their appreciation of the Ming dynasty'south obvious wealth and power past sending back to China their own riches in tribute. Appurtenances shipped out included silk, tea, painted scrolls, golden and silvery objects, textiles, carved and manufactured goods, and fine Ming porcelain. There was infinite, too, for a huge number of personnel: estimates range from 20,000 up to 32,000 expedition members on the offset voyage. These included diplomats, medical officers, astrologers, ship's crews, and military personnel which, forth with canons, bombs, and rockets, ensured the expedition could ably defend itself wherever it ventured.

The Seven Voyages of Zheng He

The first 3 voyages of Zheng He (1404, 1408 and 1409 CE) followed more than established merchandise routes. He went via Southeast Asia, sailing downwards the declension of Vietnam, stopping at Sumatra and Coffee then on through the Malay Archipelago and through the Straits of Malacca, crossing the eastern Indian Body of water to attain Bharat and Sri Lanka.

Wherever he landed, Zheng He led a delegation to the local ruler to whom he presented letters of goodwill and China's peaceful intentions towards them. He then presented a large quantity of gifts and invited the ruler to either come up in person or transport an ambassador to the courtroom of Emperor Yongle. Many rulers took upwardly the offer immediately and delegates were accommodated on Zheng He's ships to be eventually taken to Red china on the return voyage. Some rulers were not so swell, of class, notably Alagakkonara, the king of Sri Lanka, who turned out less than welcoming to these foreign visitors and tried to plunder Zheng He'south ships. Undeterred, Zheng He abducted the male monarch and brought him in person back to the Chinese imperial courtroom, where he was afterwards released after promising to pay regular tributes, which he did practice.

There were also secondary adventures besides securing new diplomatic ties. The return journeying of the first expedition, for example, saw Zheng He capture the pirate Ch'en Tsu-i, who had acquired havoc in the Malacca Straits and beyond, a feat which greatly enhanced the admiral's reputation in Southeast Asia. The second voyage on its render in 1408 CE successfully resolved a local dispute on Java. These and other actions only strengthened the view that Mainland china was the chief power in the region and its greatest source of stability.

Zheng He Fleet

Farsi Gulf & Africa

Zheng He'southward fourth voyage in 1413 CE saw him sail to Bharat again, once more pushing on around the southern tip of the subcontinent and visiting again Cochin and Calicut on the west coast. This time he also found fourth dimension to stop off at the Maldive Islands, before crossing the Arabian Sea and reaching Hormuz on the Persian Gulf. Sailing down the coast of Arabia, he so went on to Aden and up the Cerise Sea to Jeddah, from where a party travelled to Mecca. A report states that 19 foreign rulers sent tributes and diplomatic missions to the emperor as a issue of this fourth voyage.

Voyages five, six, and seven (1417, 1421, and 1431 CE) reached fifty-fifty further afield, landing at Mogadishu, Malindi, and Mombassa, all on the coast of East Africa. Zheng He is the first attested Chinese to visit the Swahili declension. The ruler of Mogadishu was responsive and did send an embassy to Yongle, and even distant Zanzibar was reached by Zheng He's fleet.

From Africa, Zheng He brought back such exotica as lions, leopards, camels, ostriches, rhinos, zebras, and giraffes. These animals caused wonder back in Red china, where the giraffe, for instance, was considered living evidence of the qilin, a sort of Chinese unicorn which represented good fortune. There is a surviving painted silk scroll from the period showing a giraffe given to the emperor by Rex Saif Al-Din Hamzah Shah of Bengal. Besides animals, Zheng He also brought dorsum gems, spices, medicines, and fine cotton cloth, as well as knowledge of strange foreign peoples and customs.

Giraffe Tribute to Emperor Yongle

Zheng He, similar many great explorers before and since, died in the eye of an expedition, his seventh voyage. The groovy admiral died in Calicut in 1433 CE, and his torso was returned to China for burying in Nanjing. Zheng He had made an incredible series of journeys, as this inscription on a tablet he erected in 1432 CE in Fujian, Prc relates:

Nosotros have traversed more than one hundred thousand li (27,000 nautical miles) of immense waterspaces and have beheld in the ocean huge waves like mountains rising sky loftier, and nosotros accept set optics on barbarian regions far away hidden in a bluish transparency of lite vapors, while our sails, loftily unfurled like clouds twenty-four hour period and nighttime, continued their course (as rapidly every bit) a star, traversing those savage waves every bit if nosotros were treading a public thoroughfare…

(quoted in von Sivers, 406)

There would exist no more than great maritime expeditions as the Chinese closed the door on the outside earth and returned to its isolationist strange policy of quondam. Yongle's successor, Xuande (r. 1426-36 CE) had initially supported Zheng's standing voyages merely he eventually put an end to the costly expeditions. The emperor even went so far as to ban the construction of any bounding main-going ships and prohibit those that existed from being used for voyages beyond Chinese littoral waters. The render to isolationism may have been due to the increased threat from the Mongols, and the huge expense of rebuilding parts of the Great Wall of Mainland china likely called for some cutbacks elsewhere. In any case, the original aim of the voyages - to secure strange tribute - was largely unsuccessful outside of Southeast Asia. The expense of the expeditions and the goods they carried did not friction match the value of the tributes that came in return. Put simply, many foreign states, although interested in the trading possibilities, did not quite concord that Cathay, the self-styled Middle Kingdom, was the eye of the world; a view confirmed past the opening upward of the New World at the other end of the aforementioned century that Zheng He had begun his voyages.

This commodity has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

0 Response to "What Impact Did Zheng He's Travels Have"

Post a Comment